-

November 19, 2015Asynchronous EverythingTweet

Midori was built out of many ultra-lightweight, fine-grained processes, connected through strongly typed message passing interfaces. It was common to see programs that’d’ve classically been single, monolithic processes – perhaps with some internal multithreading – expressed instead as dozens of small processes, resulting in natural, safe, and largely automatic parallelism. Synchronous blocking was flat-out disallowed. This meant that literally everything was asynchronous: all file and network IO, all message passing, and any “synchronization” activities like rendezvousing with other asynchronous work. The resulting system was highly concurrent, responsive to user input, and scaled like the dickens. But as you can imagine, it also came with some fascinating challenges.

Asynchronous Programming Model

The asynchronous programming model looked a lot like C#’s async/await on the surface.

That’s not a coincidence. I was the architect and lead developer on .NET tasks. As the concurrency architect on Midori, coming off just shipping the .NET release, I admit I had a bit of a bias. Even I knew what we had wouldn’t work as-is for Midori, however, so we embarked upon a multi-year journey. But as we went, we worked closely with the C# team to bring some of Midori’s approaches back to the shipping language, and had been using a variant of the async/await model for about a year when C# began looking into it. We didn’t bring all the Midori goodness to .NET, but some of it certainly showed up, mostly in the area of performance. It still kills me that I can’t go back in time and make .NET’s task a struct.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The journey to get to this point was a long one, and we should start at the beginning.

Promises

At the core of our asynchronous model was a technology called promises. These days, the idea is ubiquitous. The way we used promises, however, was more interesting, as we’ll start to see soon. We were heavily influenced by the E system. Perhaps the biggest difference compared to popular asynchronous frameworks these days is there was no cheating. There wasn’t a single synchronous API available.

The first cut at the model used explicit callbacks. This’ll be familiar to anybody who’s done Node.js programming. The idea is you get a

Promise<T>for any operation that will eventually yield aT(or fail). The operation producing that may be running asynchronously within the process or even remotely somewhere else. The consumer doesn’t need to know or care. They just deal with thePromise<T>as a first class value and, when theTis sought, must rendezvous.The basic callback model started something like this:

Promise<T> p = ... some operation ...; ... optionally do some things concurrent with that operation ...; Promise<U> u = Promise.When( p, (T t) => { ... the T is available ... }, (Exception e) => { ... a failure occurred ... } );Eventually we switched over from static to instance methods:

Promise<U> u = p.WhenResolved( (T t) => { ... the T is available ... }, (Exception e) => { ... a failure occurred ... } );Notice that the promises chain. The operation’s callbacks are expected to return a value of type

Uor throw an exception, as appropriate. Then the recipient of theupromise does the same, and so on, and so forth.This is concurrent dataflow programming. It is nice because the true dependencies of operations govern the scheduling of activity in the system. A classical system often results in work stoppage not because of true dependencies, but false dependencies, like the programmer just happening to issue a synchronous IO call deep down in the callstack, unbeknownst to the caller.

In fact, this is one of the reasons your screen bleaches so often on Windows. I’ll never forget a paper a few years back finding one of the leading causes of hangs in Outlook. A commonly used API would occasionally enumerate Postscript fonts by attempting to talk to the printer over the network. It cached fonts so it only needed to go to the printer once in a while, at unpredictable times. As a result, the “good” behavior led developers to think it safe to call from the UI thread. Nothing bad happened during testing (where, presumably, the developers worked on expensive computers with near-perfect networks). Sadly, when the network flaked out, the result was 10 second hangs with spinning donuts and bleachy white screens. To this day, we still have this problem in every OS that I use.

The issue in this example is the possibility for high latency wasn’t apparent to developers calling the API. It was even less apparent because the call was buried deep in a callstack, masked by virtual function calls, and so on. In Midori, where all asynchrony is expressed in the type system, this wouldn’t happen because such an API would necessarily return a promise. It’s true, a developer can still do something ridiculous (like an infinite loop on the UI thread), but it’s a lot harder to shoot yourself in the foot. Especially when it came to IO.

What if you didn’t want to continue the dataflow chain? No problem.

p.WhenResolved( ... as above ... ).Ignore();This turns out to be a bit of an anti-pattern. It’s usually a sign that you’re mutating shared state.

The

Ignorewarrants a quick explanation. Our language didn’t let you ignore return values without being explicit about doing so. This specificIgnoremethod also addded some diagnostics to help debug situations where you accidentally ignored something important (and lost, for example, an exception).Eventually we added a bunch of helper overloads and APIs for common patterns:

// Just respond to success, and propagate the error automatically: Promise<U> u = p.WhenResolved((T t) => { ... the T is available ... }); // Use a finally-like construct: Promise<U> u = p.WhenResolved( (T t) => { ... the T is available ... }, (Exception e) => { ... a failure occurred ... }, () => { ... unconditionally executes ... } ); // Perform various kinds of loops: Promise<U> u = Async.For(0, 10, (int i) => { ... the loop body ... }); Promise<U> u = Async.While(() => ... predicate, () => { ... the loop body ... }); // And so on.This idea is most certainly not even close to new. Joule and Alice even have nice built-in syntax to make the otherwise clumsy callback passing shown above more tolerable.

But it was not tolerable. The model tossed out decades of familiar programming language constructs, like loops.

It got really bad. Like really, really. It led to callback soup, often nested many levels deep, and often in some really important code to get right. For example, imagine you’re in the middle of a disk driver, and you see code like:

Promise<void> DoSomething(Promise<string> cmd) { return cmd.WhenResolved( s => { if (s == "...") { return DoSomethingElse(...).WhenResolved( v => { return ...; }, e => { Log(e); throw e; } ); } else { return ...; } }, e => { Log(e); throw e; } ); }It’s just impossible to follow what’s going on here. It’s hard to tell where the various returns return to, what throw is unhandled, and it’s easy to duplicate code (such as the error cases), because classical block scoping isn’t available. God forbid you need to do a loop. And it’s a disk driver – this stuff needs to be reliable!

Enter Async and Await

Almost every major language now features async and/or await-like constructs. We began wide-scale use sometime in 2009. And when I say wide-scale, I mean it.

The async/await approach let us keep the non-blocking nature of the system and yet clean up some of the above usability mess. In hindsight, it’s pretty obvious, but remember back then the most mainstream language with await used at scale was F# with its asynchronous workflows (also see this paper). And despite the boon to usability and productivity, it was also enormously controversial on the team. More on that later.

What we had was a bit different from what you’ll find in C# and .NET. Let’s walk through the progression from the promises model above to this new async/await-based one. As we go, I’ll point out the differences.

We first renamed

Promise<T>toAsyncResult<T>, and made it a struct. (This is similar to .NET’sTask<T>, however focuses more on the “data” than the “computation.”) A family of related types were born:T: the result of a prompt, synchronous computation that cannot fail.Async<T>: the result of an asynchronous computation that cannot fail.Result<T>: the result of a a prompt, synchronous computation that might fail.AsyncResult<T>: the result of an asynchronous computation that might fail.

That last one was really just a shortcut for

Async<Result<T>>.The distinction between things that can fail and things that cannot fail is a topic for another day. In summary, however, our type system guaranteed these properties for us.

Along with this, we added the

awaitandasynckeywords. A method could be markedasync:async int Foo() { ... }All this meant was that it was allowed to

awaitinside of it:async int Bar() { int x = await Foo(); ... return x * x; }Originally this was merely syntactic sugar for all the callback goop above, like it is in C#. Eventually, however, we went way beyond this, in the name of performance, and added lightweight coroutines and linked stacks. More below.

A caller invoking an

asyncmethod was forced to choose: useawaitand wait for its result, or useasyncand launch an asynchronous operation. All asynchrony in the system was thus explicit:int x = await Bar(); // Invoke Bar, but wait for its result. Async<int> y = async Bar(); // Invoke Bar asynchronously; I'll wait later. int z = await y; // ...like now. This waits for Bar to finish.This also gave us a very important, but subtle, property that we didn’t realize until much later. Because in Midori the only way to “wait” for something was to use the asynchronous model, and there was no hidden blocking, our type system told us the full set of things that could “wait.” More importantly, it told us the full set of things that could not wait, which told us what was pure synchronous computation! This could be used to guarantee no code ever blocked the UI from painting and, as we’ll see below, many other powerful capabilities.

Because of the sheer magnitude of asynchronous code in the system, we embellished lots of patterns in the language that C# still doesn’t support. For example, iterators, for loops, and LINQ queries:

IAsyncEnumerable<Movie> GetMovies(string url) { foreach (await var movie in http.Get(url)) { yield return movie; } }Or, in LINQ style:

IAsyncEnumerable<Movie> GetMovies(string url) { return from await movie in http.Get(url) ... filters ... select ... movie ...; }The entire LINQ infrastructure participated in streaming, including resource management and backpressure.

We converted millions of lines of code from the old callback style to the new async/await one. We found plenty of bugs along the way, due to the complex control flow of the explicit callback model. Especially in loops and error handling logic, which could now use the familiar programming language constructs, rather than clumsy API versions of them.

I mentioned this was controversial. Most of the team loved the usability improvements. But it wasn’t unanimous.

Maybe the biggest problem was that it encouraged a pull-style of concurrency. Pull is where a caller awaits a callee before proceeding with its own operations. In this new model, you need to go out of your way to not do that. It’s always possible, of course, thanks to the

asynckeyword, but there’s certainly a little more friction than the old model. The old, familiar, blocking model of waiting for things is just anawaitkeyword away.We offered bridges between pull and push, in the form of reactive

IObservable<T>/IObserver<T>adapters. I wouldn’t claim they were very successful, however for side-effectful actions that didn’t employ dataflow, they were useful. In fact, our entire UI framework was based on the concept of functional reactive programming, which required a slight divergence from the Reactive Framework in the name of performance. But alas, this is a post on its own.An interesting consequence was a new difference between a method that awaits before returning a

T, and one that returns anAsync<T>directly. This difference didn’t exist in the type system previously. This, quite frankly, annoyed the hell out of me and still does. For example:async int Bar() { return await Foo(); } Async<int> Bar() { return async Foo(); }We would like to claim the performance between these two is identical. But alas, it isn’t. The former blocks and keeps a stack frame alive, whereas the latter does not. Some compiler cleverness can help address common patterns – this is really the moral equivalent to an asynchronous tail call – however it’s not always so cut and dry.

On its own, this wasn’t a killer. It caused some anti-patterns in important areas like streams, however. Developers were prone to awaiting in areas they used to just pass around

Async<T>s, leading to an accumulation of paused stack frames that really didn’t need to be there. We had good solutions to most patterns, but up to the end of the project we struggled with this, especially in the networking stack that was chasing 10GB NIC saturation at wire speed. We’ll discuss some of the techniques we employed below.But at the end of this journey, this change was well worth it, both in the simplicity and usability of the model, and also in some of the optimization doors it opened up for us.

The Execution Model

That brings me to the execution model. We went through maybe five different models, but landed in a nice place.

A key to achieving asynchronous everything was ultra-lightweight processes. This was possible thanks to software isolated processes (SIPs), building upon the foundation of safety described in an earlier post.

The absence of shared, mutable static state helped us keep processes small. It’s surprising how much address space is burned in a typical program with tables and mutable static variables. And how much startup time can be spent initializing said state. As I mentioned earlier, we froze most statics as constants that got shared across many processes. The execution model also resulted in cheaper stacks (more on that below) which was also a key factor. The final thing here that helped wasn’t even technical, but cultural. We measured process start time and process footprint nightly in our lab and had a “ratcheting” process where every sprint we ensured we got better than last sprint. A group of us got in a room every week to look at the numbers and answer the question of why they went up, down, or stayed the same. We had this culture for performance generally, but in this case, it kept the base of the system light and nimble.

Code running inside processes could not block. Inside the kernel, blocking was permitted in select areas, but remember no user code ever ran in the kernel, so this was an implementation detail. And when I say “no blocking,” I really mean it: Midori did not have demand paging which, in a classical system, means that touching a piece of memory may physically block to perform IO. I have to say, the lack of page thrashing was such a welcome that, to this day, the first thing I do on a new Windows sytem is disable paging. I would much rather have the OS kill programs when it is close to the limit, and continue running reliably, than to deal with a paging madness.

C#’s implementation of async/await is entirely a front-end compiler trick. If you’ve ever run ildasm on the resulting assembly, you know: it lifts captured variables into fields on an object, rewrites the method’s body into a state machine, and uses Task’s continuation passing machinery to keep the iterator-like object advancing through the states.

We began this way and shared some of our key optimizations with the C# and .NET teams. Unfortunately, the result at the scale of what we had in Midori simply didn’t work.

First, remember, Midori was an entire OS written to use garbage collected memory. We learned some key lessons that were necessary for this to perform adequately. But I’d say the prime directive was to avoid superfluous allocations like the plague. Even short-lived ones. There is a mantra that permeated .NET in the early days: Gen0 collections are free. Unfortunately, this shaped a lot of .NET’s library code, and is utter hogwash. Gen0 collections introduce pauses, dirty the cache, and introduce beat frequency issues in a highly concurrent system. I will point out, however, one of the tricks to garbage collection working at the scale of Midori was precisely the fine-grained process model, where each process had a distinct heap that was independently collectible. I’ll have an entire article devoted to how we got good behavior out of our garbage collector, but this was the most important architectural characteristic.

The first key optimization, therefore, is that an async method that doesn’t await shouldn’t allocate anything.

We were able to share this experience with .NET in time for C#’s await to ship. Sadly, by then, .NET’s Task had already been made a class. Since .NET requires async method return types to be Tasks, they cannot be zero-allocation unless you go out of your way to use clumsy patterns like caching singleton Task objects.

The second key optimization was to ensure that async methods that awaited allocated as little as possible.

In Midori, it was very common for one async method to invoke another, which invoked another … and so on. If you think about what happens in the state machine model, a leaf method that blocks triggers a cascade of O(K) allocations, where K is the depth of the stack at the time of the await. This is really unfortunate.

What we ended up with was a model that only allocated when the await happened, and that allocated only once for an entire such chain of calls. We called this chain an “activity.” The top-most

asyncdemarcated the boundary of an activity. As a result,asynccould cost something, butawaitwas free.Well, that required one additional step. And this one was the biggie.

The final key optimization was to ensure that async methods imposed as little penalty as possible. This meant eliminating a few sub-optimal aspects of the state machine rewrite model. Actually, we abandoned it:

-

It completely destroyed code quality. It impeded simple optimizations like inlining, because few inliners consider a switch statement with multiple state variables, plus a heap-allocated display frame, with lots of local variable copying, to be a “simple method.” We were competing with OS’s written in native code, so this matters a lot.

-

It required changes to the calling convention. Namely, returns had to be

Async*<T>objects, much like .NET’sTask<T>. This was a non-starter. Even though ours were structs – eliminating the allocation aspect – they were multi-words, and required that code fetch out the values with state and type testing. If my async method returns an int, I want the generated machine code to be a method that returns an int, goddamnit. -

Finally, it was common for too much heap state to get captured. We wanted the total space consumed by an awaiting activity to be as small as possible. It was common for some processes to end up with hundreds or thousands of them, in addition to some processes constantly switching between them. For footprint and cache reasons, it was important that they remain as small as the most carefully hand-crafted state machine as possible.

The model we built was one where asynchronous activities ran on linked stacks. These links could start as small as 128 bytes and grow as needed. After much experimentation, we landed on a model where link sizes doubled each time; so, the first link would be 128b, then 256b, …, on up to 8k chunks. Implementing this required deep compiler support. As did getting it to perform well. The compiler knew to hoist link checks, especially out of loops, and probe for larger amounts when it could predict the size of stack frames (accounting for inlining). There is a common problem with linking where you can end up relinking frequently, especially at the edge of a function call within a loop, however most of the above optimizations prevented this from showing up. And, even if they did, our linking code was hand-crafted assembly – IIRC, it was three instructions to link – and we kept a lookaside of hot link segments we could reuse.

There was another key innovation. Remember, I hinted earlier, we knew statically in the type system whether a function was asynchronous or not, simply by the presence of the

asynckeyword? That gave us the ability in the compiler to execute all non-asynchronous code on classical stacks. The net result was that all synchronous code remained probe-free! Another consequence is the OS kernel could schedule all synchronous code on a set of pooled stacks. These were always warm, and resembled a classical thread pool, more than an OS scheduler. Because they never blocked, you didn’t have O(T) stacks, where T is the number of threads active in the entire system. Instead, you ended up with O(P), where P is the number of processors on the machine. Remember, eliminating demand paging was also key to achieiving this outcome. So it was really a bunch of “big bets” that added up to something that was seriously game-changing.Message Passing

A fundamental part of the system has been missing from the conversation: message passing.

Not only were processes ultra-lightweight, they were single-threaded in nature. Each one ran an event loop and that event loop couldn’t be blocked, thanks to the non-blocking nature of the system. Its job was to execute a piece of non-blocking work until it finished or awaited, and then to fetch the next piece of work, and so on. An await that was previously waiting and became satisfied was simply scheduled as another turn of the crank.

Each such turn of the crank was called, fittingly, a “turn.”

This meant that turns could happen between asynchronous activities and at await points, nowhere else. As a result, concurrent interleaving only occurred at well-defined points. This was a giant boon to reasoning about state in the face of concurrency, however it comes with some gotchas, as we explore later.

The nicest part of this, however, was that processes suffered no shared memory race conditions.

We did have a task and data parallel framework. It leveraged the concurrency safety features of the languge I’ve mentioned previously – immutability, isolation, and readonly annotations – to ensure that this data race freedom was not violated. This was used for fine-grained computations that could use the extra compute power. Most of the system, however, gained its parallel execution through the decomposition into processes connected by message passing.

Each process could export an asynchronous interface. It looked something like this:

async interface ICalculator { async int Add(int x, int y); async int Multiply(int x, int y); // Etc... }As with most asynchronous RPC systems, from this interface was generated a server stub and client-side proxy. On the server, we would implement the interface:

class MyCalculator : ICalculator { async int Add(int x, int y) { return x + y; } async int Multiply(int x, int y) { return x * y; } // Etc... }Each server-side object could also request capabilities simply by exposing a constructor, much like the program’s main entrypoint could, as I described in the prior post. Our application model took care of activating and wiring up the server’s programs and services.

A server could also return references to other objects, either in its own process, or a distant one. The system managed the object lifetime state in coordination with the garbage collector. So, for example, a tree:

class MyTree : ITree { async ITree Left() { ... } async ITree Right() { ... } }As you might guess, the client-side would then get its hands on a proxy object, connected to this server object running in a process. It’s possible the server would be in the same process as the client, however typically the object was distant, because this is how processes communicated with one another:

class MyProgram { async void Main(IConsole console, ICalculator calc) { var result = await calc.Add(2, 2); await console.WriteLine(result); } }Imagining for a moment that the calculator was a system service, this program would communicate with that system service to add two numbers, and then print the result to the console (which itself also could be a different service).

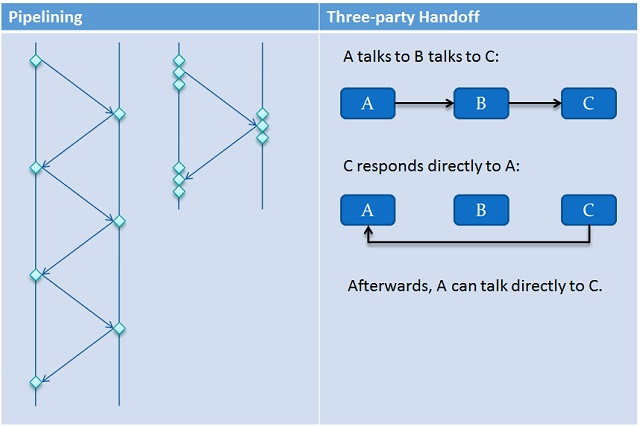

A few key aspects of the system made message passing very efficient. First, all of the data structures necessary to talk cross-process were in user-mode, so no kernel-mode transitions were needed. In fact, they were mostly lock-free. Second, the system used a technique called “pipelining” to remove round-trips and synchronization ping-ponging. Batches of messages could be stuffed into channels before they filled up. They were delivered in chunks at-a-time. Finally, a novel technique called “three-party handoff” was used to shorten the communication paths between parties engaging in a message passing dialogue. This cut out middle-men whose jobs in a normal system would have been to simply bucket brigade the messages, adding no value, other than latency and wasted work.

The only types marshalable across message passing boundaries were:

- Primitive types (

int,string, etc). - Custom PODs that didn’t contain pointers (explicitly labeled marshalable).

- References to streams (see below).

- References to other async objects (e.g., our

ICalculatorabove). - A special

SharedDataobject, which requires a bit more explanation.

Most of these are obvious. The

SharedDatathing is a little subtle, however. Midori had a fundamental philosophy of “zero-copy” woven throughout its fabric. This will be the topic of a future post. It’s the secret sauce that let us out-perform many classical systems on some key benchmarks. The idea is, however, no byte should be copied if it can be avoided. So we don’t want to marshal abyte[]by copy when sending a message between processes, for example. TheSharedDatawas a automatic ref-counted pointer to some immutable data in a heap shared between processes. The OS kernel managed this heap memory and reclaimed it when all references dropped to zero. Because the ref-counts were automatic, programs couldn’t get it wrong. This leveraged some new features in our language, like destructors.We also had the notion of “near objects,” which went an extra step and let you marshal references to immutable data within the same process heap. This let you marshal rich objects by-reference. For example:

// An asynchronous object in my heap: ISpellChecker checker = ...; // A complex immutable Document in my heap, // perhaps using piece tables: immutable Document doc = ...; // Check the document by sending messages within // my own process; no copies are necessary: var results = await checker.Check(doc);As you can guess, all of this was built upon a more fundamental notion of a “channel.” This is similar to what you’ll see in Occam, Go and related CSP languages. I personally found the structure and associated checking around how messages float around the system more comfortable than coding straight to the channels themselves, but your mileage may vary. The result felt similar to programming with actors, with some key differences around the relationship between process and object identity.

Streams

Our framework had two fundamental stream types:

Streamheld a stream of bytes andSequence<T>heldTs. They were both forward-only (we had separate seekable classes) and 100% asynchronous.Why two types, you wonder? They began as entirely independent things, and eventually converged to be brother and sister, sharing a lot of policy and implementation with one another. The core reason they remained distinct, however, is that it turns out when you know you’re just schlepping raw byte-streams around, you can make a lot of interesting performance improvements in the implementation, compared to a fully generic version.

For purposes of this discussion, however, just imagine that

StreamandSequence<byte>are isomorphic.As hinted at earlier, we also had

IAsyncEnumerable<T>andIAsyncEnumerator<T>types. These were the most general purpose interfaces you’d code against when wanting to consume something. Developers could, of course, implement their own stream types, especially since we had asynchronous iterators in the language. A full set of asynchronous LINQ operators worked over these interfaces, so LINQ worked nicely for consuming and composing streams and sequences.In addition to the enumerable-based consumption techniques, all the standard peeking and batch-based APIs were available. It’s important to point out, however, that the entire streams framework built atop the zero-copy capabilities of the kernel, to avoid copying. Every time I see an API in .NET that deals with streams in terms of

byte[]s makes me shed a tear. The result is our streams were actually used in very fundamental areas of the system, like the network stack itself, the filesystem the web servers, and more.As hinted at earlier, we supported both push and pull-style concurrency in the streaming APIs. For example, we supported generators, which could either style:

// Push: var s = new Stream(g => { var item = ... do some work ...; g.Push(item); }); // Pull: var s = new Stream(g => { var item = await ... do some work ...; yield return item; });The streaming implementation handled gory details of batching and generally ensuring streaming was as efficient as possible. A key technique was flow control, borrowed from the world of TCP. A stream producer and consumer collaborated, entirely under the hood of the abstraction, to ensure that the pipeline didn’t get too imbalanced. This worked much like TCP flow control by maintaining a so-called “window” and opening and closing it as availability came and went. Overall this worked great. For example, our realtime multimedia stack had two asynchronous pipelines, one for processing audio and the other for processing video, and merged them together, to implement A/V sync. In general, the built-in flow control mechanisms were able to keep them from dropping frames.

“Grand” Challenges

The above was a whirlwind tour. I’ve glossed over some key details, but hopefully you get the picture.

Along this journey we uncovered several “grand challenges.” I’ll never forget them, as they formed the outline of my entire yearly performance review for a good 3 years straight. I was determined to conquer them. I can’t say that our answers were perfect, but we made a gigantic dent in them.

Cancellation

The need to have cancellable work isn’t anything new. I came up with the

CancellationTokenabstraction in .NET, largely in response to some of the challenges we had around ambient authority with prior “implicitly scoped” attempts.The difference in Midori was the scale. Asynchronous work was everywhere. It sprawled out across processes and, sometimes, even machines. It was incredibly difficult to chase down run-away work. My simple use-case was how to implement the browser’s “cancel” button reliably. Simply rendering a webpage involved a handful of the browser’s own processes, plus the various networking processes – including the NIC’s device driver – along with the UI stack, and more. Having the ability to instantly and reliably cancel all of this work was not just appealing, it was required.

The solution ended up building atop the foundation of

CancellationToken.They key innovation was first to rebuild the idea of

CancellationTokenon top of our overall message passing model, and then to weave it throughout in all the right places. For example:- CancellationTokens could extend their reach across processes.

- Whole async objects could be wrapped in a CancellationToken, and used to trigger revocation.

- Whole async functions could be invoked with a CancellationToken, such that cancelling propagated downward.

- Areas like storage needed to manually check to ensure that state was kept consistent.

In summary, we took a “whole system” approach to the way cancellation was plumbed throughout the system, including extending the reach of cancellation across processes. I was happy with where we landedon this one.

State Management

The ever-problematic “state management” problem can be illustrated with a simple example:

async void M(State s) { int x = s.x; await ... something ...; assert(x == s.x); }The question here is, can the assertion fire?

The answer is obviously yes. Even without concurrency, reentrancy is a problem. Depending on what I do in “… something …”, the

Stateobject pointed to bysmight change before returning back to us.But somewhat subtly, even if “… something …” doesn’t change the object, we may find that the assertion fires. Consider a caller:

State s = ...; Async<void> a = async M(s); s.x++; await a;The caller retains an alias to the same object. If M’s awaiting operation must wait, control is resumed to the caller. The caller here then increments

xbefore awaiting M’s completion. Unfortunately, when M resumes, it will discover that the value ofxno longer matchess.x.This problem manifests in other more devious ways. For example, imagine one of those server objects earlier:

class StatefulActor : ISomething { int state; async void A() { // Use state } async void B() { // Use state } }Imagining that both A and B contain awaits, they can now interleave with one another, in addition to interleaving with multiple activations of themselves. If you’re thinking this smells like a race condition, you’re right. In fact, saying that message passing systems don’t have race conditions is an outright lie. There have even been papers discussing this in the context of Erlang. It’s more correct to say our system didn’t have data race conditions.

Anyway, there be dragons here.

The solution is to steal a page from classical synchronization, and apply one of many techniques:

- Isolation.

- Standard synchronization techniques (prevent write-write or read-write hazards).

- Transactions.

By far, we preferred isolation. It turns out web frameworks offer good lessons to learn from here. Most of the time, a server object is part of a “session” and should not be aliased across multiple concurrent clients. It tended to be easy to partition state into sub-objects, and have dialogues using those. Our language annotations around mutability helped to guide this process.

A lesser regarded technique was to apply synchronization. Thankfully in our language, we knew which operations read versus wrote, and so we could use that to block dispatching messages intelligently, using standard reader-writer lock techniques. This was comfy and cozy and whatnot, but could lead to deadlocks if done incorrectly (which we did our best to detect). As you can see, once you start down this path, the world is less elegant, so we discouraged it.

Finally, transactions. We didn’t go there. Distributed transactions are evil.

In general, we tried to learn from the web, and apply architectures that worked for large-scale distributed systems. Statelessness was by far the easiest pattern. Isolation was a close second. Everything else was just a little dirty.

P.S. I will be sure to have an entire post dedicated to the language annotations.

Ordering

In a distributed system, things get unordered unless you go out of your way to preserve order. And going out of your way to preserve order removes concurrency from the system, adds book-keeping, and a ton of complexity. My biggest lesson learned here was: distributed systems are unordered. It sucks. Don’t fight it. You’ll regret trying.

Leslie Lamport has a classic must-read paper on the topic: Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System.

But unordered events surprise developers. A good example is as follows:

// Three asynchronous objects: IA a = ...; IB b = ...; IC c = ...; // Tell b to talk to a: var req1 = async b.TalkTo(a); // Tell c to talk to b: var req2 = async c.TalkTo(a); await Async.Join(req1, req2);If you expected that

bis guaranteed to talk withabeforectalks witha, you’re in for a bad day.We offered facilities for controlling order. For example, you could flush all the messages from a channel, and await their delivery. You could, of course, always await the individual operations, but this introduces some amount of unnecessary latency due to round-tripping. We also had a “flow” abstraction that let you guarantee a sequence of asynchronous messages were delivered in order, but in the most efficient way possible.

As with state management, we found that an abundance of ordering problems was often indicative of a design problem.

Debugging

With so much work flying around in the system, debugging was a challenge in the early days.

The solution, as with many such challenges, was tooling. We taught our tools that activities were as first class as threads. We introduced causality IDs that flowed with messages across processes, so if you broke into a message dispatch in one process, you could trace back to the origin in potentially some other distant process. The default behavior for a crash was to gather this cross-process stack trace, to help figure out how you go to where you were.

Another enormous benefit of our improved execution model was that stacks were back! Yes, you actually got stack traces for asynchronous activities awaiting multiple levels deep at no extra expense. Many systems like .NET’s have to go out of their way to piece together a stack trace from disparate hunks of stack-like objects. We had that challenge across processes, but within a single process, all activities had normal stack traces with variables that were in a good state.

Resource Management

At some point, I had a key realization. Blocking in a classical system acts as a natural throttle on the amount of work that can be offered up to the system. Your average program doesn’t express all of its latent concurrency and parallelism by default. But ours did! Although that sounds like a good thing – and indeed it was – it came with a dark side. How the heck do you manage resources and schedule all that work intelligently, in the face of so much of it?

This was a loooooooong, winding road. I won’t claim we solved it. I won’t claim we even came close. I will claim we tackled it enough that the problem was less disastrous to the stability of the system than it would have otherwise been.

An analogous problem that I’ve faced in the past is with thread pools in both Windows and the .NET Framework. Given that work items might block in the thread pool, how do you decide the number of threads to keep active at once? There are always imperfect heuristics applied, and I would say we did no worse. If anything, we erred on the side of using more of the latent parallelism to saturate the available resources. It was pretty common to be running the Midori system at 100% CPU utilization, because it was doing useful stuff, which is pretty rare on PCs and traditional apps.

But the scale of our problem was much worse than anything I’d ever seen. Everything was asynchronous. Imagine an app traversing the entire filesystem, and performing a series of asynchronous operations for each file on disk. In Midori, the app, filesystem, disk drivers, etc., are all different asynchronous processes. It’s easy to envision the resulting fork bomb-like problem that results.

The solution here broke down into a two-pronged defense:

- Self-control: async code knows that it could flood the system with work, and explicitly tries not to.

- Automatic resource management: no matter what the user-written code does, the system can throttle automatically.

For obvious reasons, we preferred automatic resource management.

This took the form of the OS scheduler making decisions about which processes to visit, which turns to let run, and, in some cases, techniques like flow control as we saw above with streams. This is the area we had the most “open ended” and “unresolved” research. We tried out many really cool ideas. This included attempting to model the expected resource usage of asynchronous activities (similar to this paper on convex optimization). That turned out to be very difficult, but certainly shows some interesting long turn promise if you can couple it with adaptive techniques. Perhaps surprisingly, our most promising results came from adapting advertisement bidding algorithms to resource allocation. Coupled with an element of game theory, this approach gets very interesting. If the system charges a market value for all system resources, and all agents in the system have a finite amount of “purchasing power,” we can expect they will purchase those resources that benefit themselves the most based on the market prices available.

But automatic management wasn’t always perfect. That’s where self-control came in. A programmer could also help us out by capping the maximum number of outstanding activities, using simple techniques like “wide-loops.” A wide-loop was an asynchronous loop where the developer specified the maximum outstanding iterations. The system ensured it launched no more than this count at once. It always felt a little cheesy but, coupled with resource management, did the trick.

I would say we didn’t die from this one. We really thought we would die from this one. I would also say it was solved to my least satisfaction out of the bunch, however. It remains fertile ground for innovative systems research.

Winding Down

That was a lot to fit into one post. As you can see, we took “asynchronous everywhere” to quite the extreme.

In the meantime, the world has come a long way, much closer to this model than when we began. In Windows 8, a large focus was the introduction of asynchronous APIs, and, like with adding await to C#, we gave them our own lessons learned at the time. A little bit of what we were doing rubbed off, but certainly nothing to the level of what’s above.

The resulting system was automatically parallel in a very different way than the standard meaning. Tons of tiny processes and lots of asynchronous messages ensured the system kept making forward progress, even in the face of variable latency operations like networking. My favorite demo we ever gave, to Steve Ballmer, was a mock implementation of Skype on our own multimedia stack that wouldn’t hang even if you tried your hardest to force it.

As much as I’d like to keep going on architecture and programming model topics, I think I need to take a step back. Our compiler keeps coming up and, in many ways, it was our secret sauce. The techniques we used there enabled us to achieve all of these larger goals. Without that foundation, we’d never have had the safety or been on the same playing ground as native code. See you next time, when we nerd out a bit on compilers.