-

December 27, 2013C# for Systems ProgrammingTweet

My team has been designing and implementing a set of “systems programming” extensions to C# over the past 4 years. At long last, I’ll begin sharing our experiences in a series of blog posts.

The first question is, “Why a new language?” I will readily admit that world already has a plethora of them.

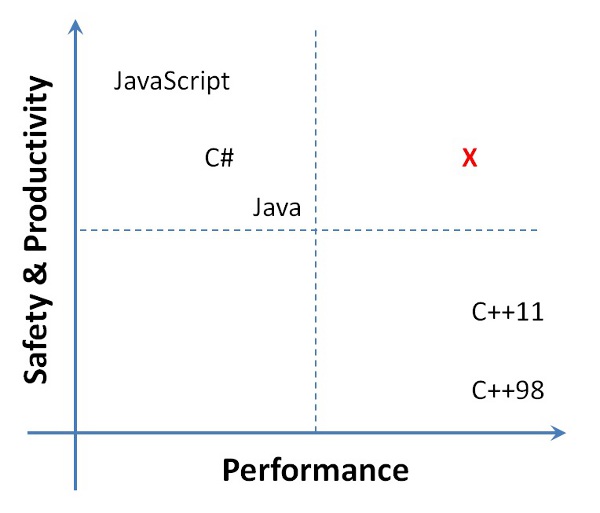

I usually explain it as follows. If you were to draw a spectrum of popular languages, with axes being “Safety & Productivity” and “Performance,” you might draw it something like this:

(Please take this with a grain of salt. I understand that Safety != Productivity (though they certainly go hand-in-hand – having seen how much time and energy is typically spent with safety bugs, lint tools, etc.), that there are many kinds of safety, etc.)

Well, I claim there are really two broad quadrants dominating our language community today.

In the upper-left, you’ve got garbage collected languages that place a premium on developer productivity. Over the past few years, JavaScript performance has improved dramatically, thanks to Google leading the way and showing what is possible. Recently, folks have done the same with PHP. It’s clear that there’s a whole family of dynamically typed languages that are now giving languages like C# and Java a run for their money. The choice is now less about performance, and more about whether you want a static type system.

This does mean that languages like C# are increasingly suffering from the Law of the Excluded Middle. The middle’s a bad place to be.

In the lower-right, you’ve got pedal-to-the-metal performance. Let’s be honest, most programmers wouldn’t place C# and Java in the same quadrant, and I agree. I’ve seen many people run away from garbage collection back to C++, with a sour taste permeating their mouths. (To be fair, this is only partly due to garbage collection itself; it’s largely due to poor design patterns, frameworks, and a lost opportunity to do better in the language.) Java is closer than C# thanks to the excellent work in HotSpot-like VMs which employ code pitching and stack allocation. But still, most hard-core systems programmers still choose C++ over C# and Java because of the performance advantages. Despite C++11 inching closer to languages like C# and Java in the areas of productivity and safety, it’s an explicit non-goal to add guaranteed type-safety to C++. You encounter the unsafety far less these days, but I am a firm believer that, as with pregnancy, “you can’t be half-safe.” Its presence means you must always plan for the worst case, and use tools to recover safety after-the-fact, rather than having it in the type system.

Our top-level goal was to explore whether you really have to choose between these quadrants. In other words, is there a sweet spot somewhere in the top-right? After multiple years’ of work, including applying this to an enormous codebase, I believe the answer is “Yes!”

The result should be seen more of a set of extensions to C# – with minimal breaking changes – than a completely new language.

The next question is, “Why base it on C#?” Type-safety is a non-negotiable aspect of our desired language, and C# represents a pretty darn good “modern type-safe C++” canvas on which to begin painting. It is closer to what we want than, say, Java, particularly because of the presence of modern features like lambdas and delegates. There are other candidate languages in this space, too, these days, most notably D, Rust, and Go. But when we began, these languages had either not surfaced yet, or had not yet invested significantly in our intended areas of focus. And hey, my team works at Microsoft, where there is ample C# talent and community just an arm’s length away, particularly in our customer-base. I am eager to collaborate with experts in these other language communities, of course, and have already shared ideas with some key people. The good news is that our lineage stems from similar origins in C, C++, Haskell, and deep type-systems work in the areas of regions, linearity, and the like.

Finally, you might wonder, “Why not base it on C++?” As we’ve progressed, I do have to admit that I often wonder whether we should have started with C++, and worked backwards to carve out a “safe subset” of the language. We often find ourselves “tossing C# and C++ in a blender to see what comes out,” and I will admit at times C# has held us back. Particularly when you start thinking about RAII, deterministic destruction, references, etc. Generics versus templates is a blog post of subtleties in its own right. I do expect to take our learnings and explore this avenue at some point, largely for two reasons: (1) it will ease portability for a larger number of developers (there’s a lot more C++ on Earth than C#), and (2) I dream of standardizing the ideas, so that the OSS community also does not need to make the difficult “safe/productive vs. performant” decision. But for the initial project goals, I am happy to have begun with C#, not the least reason for which is the rich .NET frameworks that we could use as a blueprint (noting that they needed to change pretty heavily to satisfy our goals).

I’ve given a few glimpses into this work over the years (see here and here, for example). In the months to come, I will start sharing more details. My goal is to eventually open source this thing, but before we can do that we need to button up a few aspects of the language and, more importantly, move to the Roslyn code-base so the C# relationship is more elegant. Hopefully in 2014.

At a high level, I classify the language features into six primary categories:

1) Lifetime understanding. C++ has RAII, deterministic destruction, and efficient allocation of objects. C# and Java both coax developers into relying too heavily on the GC heap, and offers only “loose” support for deterministic destruction via IDisposable. Part of what my team does is regularly convert C# programs to this new language, and it’s not uncommon for us to encounter 30-50% time spent in GC. For servers, this kills throughput; for clients, it degrades the experience, by injecting latency into the interaction. We’ve stolen a page from C++ – in areas like rvalue references, move semantics, destruction, references / borrowing – and yet retained the necessary elements of safety, and merged them with ideas from functional languages. This allows us to aggressively stack allocate objects, deterministically destruct, and more.

2) Side-effects understanding. This is the evolution of what we published in OOPSLA 2012, giving you elements of C++ const (but again with safety), along with first class immutability and isolation.

3) Async programming at scale. The community has been ‘round and ‘round on this one, namely whether to use continuation-passing or lightweight blocking coroutines. This includes C# but also pretty much every other language on the planet. The key innovation here is a composable type-system that is agnostic to the execution model, and can map efficiently to either one. It would be arrogant to claim we’ve got the one right way to expose this stuff, but having experience with many other approaches, I love where we landed.

4) Type-safe systems programming. It’s commonly claimed that with type-safety comes an inherent loss of performance. It is true that bounds checking is non-negotiable, and that we prefer overflow checking by default. It’s surprising what a good optimizing compiler can do here, versus JIT compiling. (And one only needs to casually audit some recent security bulletins to see why these features have merit.) Other areas include allowing you to do more without allocating. Like having lambda-based APIs that can be called with zero allocations (rather than the usual two: one for the delegate, one for the display). And being able to easily carve out sub-arrays and sub-strings without allocating.

5) Modern error model. This is another one that the community disagrees about. We have picked what I believe to be the sweet spot: contracts everywhere (preconditions, postconditions, invariants, assertions, etc), fail-fast as the default policy, exceptions for the rare dynamic failure (parsing, I/O, etc), and typed exceptions only when you absolutely need rich exceptions. All integrated into the type system in a 1st class way, so that you get all the proper subtyping behavior necessary to make it safe and sound.

6) Modern frameworks. This is a catch-all bucket that covers things like async LINQ, improved enumerator support that competes with C++ iterators in performance and doesn’t demand double-interface dispatch to extract elements, etc. To be entirely honest, this is the area we have the biggest list of “designed but not yet implemented features”, spanning things like void-as-a-1st-class-type, non-null types, traits, 1st class effect typing, and more. I expect us to have a handful in our mid-2014 checkpoint, but not very many.

Assuming there’s interest, I am eager to hear what you think, get feedback on the overall idea (as well as the specifics), and also find out what aspects folks would like to hear more about. I am excited to share, however the reality is that I won’t have a ton of time to write in the months ahead; we still have an enormous amount of work to do (oh, we’re hiring ;-)). But I’d sure love for y’all to help me prioritize what to share and in what order. Ultimately, I eagerly await the day when we can share real code. In the meantime, Happy Hacking!